Deerfield-News.com-Deerfield Beach, Fl-LAST TIME I HAD THE GOVERNMENT VIOLATE MY CONSTITUTIONAL RIGHTS THIS IS WHAT WE DID SUED IN FEDERAL COURT FILED A CONSTITUTIONAL CHALLENGE AGAINST THE COMMONWEALTH OF PUERTO RICO AND WON..

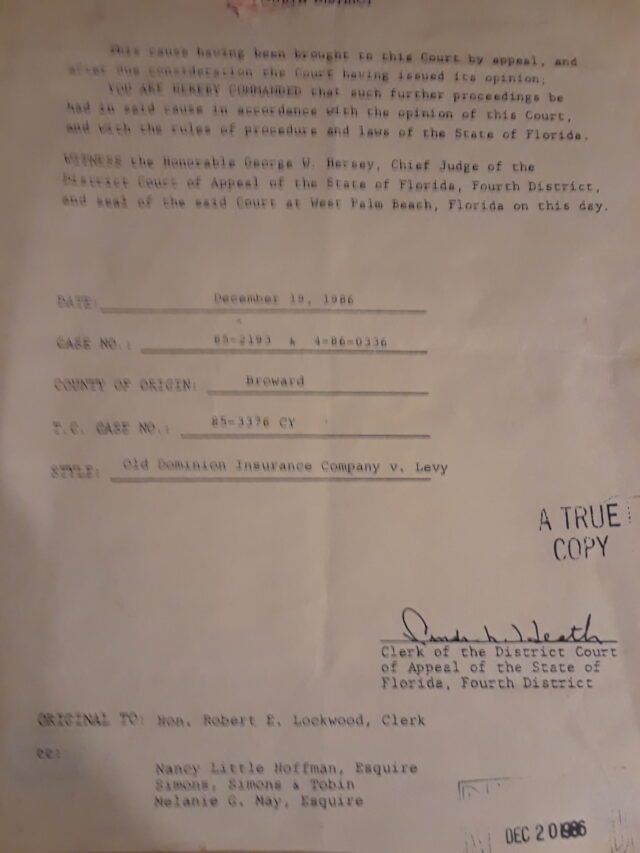

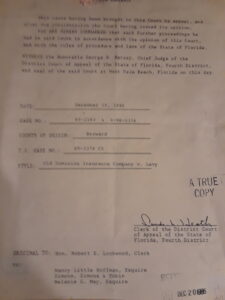

THE LAST TIME AN INSURANCE COMPANY “OLD DOMINION” TRIED TO SUE ME TO ESCAPE UNINSURED MOTORIST COVERAGE I HAD BOUGHT FROM THEM.

I HIRED SOME OF BROWARD’S BEST SIMONS, SIMONS AND TOBIN AND NANCY LITTLE HOFFMAN FOR THE APPEAL AND WIN PER CURIAM AFFIRMED.

THEN WE SET A PRECEDENT THAT STILL STANDS TODAY EXTENDING THE STATUTE OF LIMITATIONS ON A PIP CASE TO 5 YEARS AND DATE OF BREACH OF CONTRACT ANOTHER GREAT JOB BY BROWARD ATTORNEYS GREVIOR AND JORDAN WITH WAYNE KOPPEL WINNING A REVERSAL AT THE 4TH DISTRICT COURT OF APPEALS

TODAY I HAVE TO CONTEMPLATE SUING BUDDY SPARROW WHOSE REAL NAME IS LAWRENCE CASTALDI A LOCAL BUSINESSMAN OWNER OF CLOSET MAVEN INC. FOR COPYRIGHT INFRINGEMENT AMONGST OTHER THINGS JUST TO LET BUDDY KNOW I HAVE SOME GREAT LAWYERS IN PUERTO RICO AND FORT LAUDERDALE.

Used Tire News-Deerfield Beach,Fl-Usedtires.com via Used Tire International was subject to law 171 of 1996 instituted in Puerto Rico regulating the sale of used tires and establishing a scrap tire recycling program. Used Tire international the moment the law took effect sought relief from the federal court.

Used Tire International sought an injunction along with a Temporary Restraining Order barring the government of Puerto Rico from enforcing the challenged portions of the law. The jist of this law was written by new tire makers and their resellers, in Puerto Rico to stop used tires from the outside from coming into Puerto Rico.

This is a long read but worth it if you believe in the constitution.

United States Court of Appeals, First Circuit.

USED TIRE INTERNATIONAL, INC., Plaintiff, Appellant, v. Manuel DIAZ-SALDAÑA, Defendant, Appellee.

USED TIRE INTERNATIONAL, INC., Plaintiff, Appellee, v. Manuel DIAZ-SALDAÑA, Defendant, Appellant.

Nos. 97-2347, 97-2348.

Decided: September 11, 1998

Before SELYA and BOUDIN, Circuit Judges, and SCHWARZER,* Senior District Judge. Sylvia Roger-Stefani, Assistant Solicitor General, with whom Carlos Lugo-Fiol, Solicitor General, and Edda Serrano-Blasini, Deputy Solicitor General, Federal Litigation Division, Puerto Rico Department of Justice, were on brief, for appellant. Joan S. Peters, with whom Andrés Guillemard-Noble and Nachman, Guillemard & Rebollo were on brief, for appellee.

In an effort to attack the mounting problem of solid waste disposal, the Puerto Rico legislature in 1996 enacted the Tire Handling Act, also known as Law 171. This act establishes a comprehensive scheme for the handling and disposal of used tires. Among other things, it requires tire vendors to accept customers’ used tires at no extra charge for processing or disposal, prohibits the burning of tires and depositing of tires in landfills except under certain conditions, regulates the storage and recycling of tires, establishes import fees, sets up a fund for handling scrap tires, creates incentives for recycling and developing alternative uses for scrap tires, and imposes penalties for noncompliance with its provisions. The legislature identified the disposal of tires as a particular problem because of the fire hazard they present, the public health hazard they create from disease-carrying mosquitoes breeding in water that accumulates inside discarded tires and the large amount of space they occupy, diminishing the useful life of landfills.

Used Tire International, Inc. (“UTI”) is an importer of used tires into Puerto Rico. It brought this action for declaratory and injunctive relief against appellant Manuel DíazSaldaña as Secretary of the Treasury to bar enforcement of certain provisions of Law 171. Those provisions are: Article 5(B) which prohibits the import of tires that do not have a minimum tread depth of 3/32”; Article 5(D) which requires tire importers to file a bond in an amount equivalent to the cost of handling and disposing of the imported product and provides for execution of the bond in the event that 10% of a representative sample of a shipment does not qualify; Article 6 which imposes a charge on all imported tires; Article 17(A)(1) which provides for distributions from a tire handling fund, created from the charge imposed on importers of tires, to recyclers, processors and exporters of tires; and Article 19(A) which imposes a $10.00 fine on persons selling or importing tires that do not have a minimum tread depth of 3/32.” Following a hearing on UTI’s request for a preliminary injunction at which both sides presented testimony, the district court issued an opinion and order, granting the injunction against enforcement of Articles 5(B), 5(D) and 19(A) and denying it with respect to Articles 6 and 17(A)(1). Puerto Rico appealed the order and UTI cross-appealed. The parties have stipulated that we may treat Puerto Rico’s appeal as being from a final adjudication of the invalidity of Articles 5(B), 5(D) and 19(A). We have jurisdiction under 28 U.S.C. §§ 1331 and 1292(a)(1).

PUERTO RICO’S APPEAL

The district court concluded that Articles 5(B) and 19(A) facially discriminate against interstate commerce by banning the importation of a class of tires that may be legally sold and used in Puerto Rico. In reaching that conclusion it rejected the Secretary’s argument that Law 171 is non-discriminatory because the 3/32” requirement applies equally to importers and sellers of used tires. The argument was premised on the first sentence of Article 19(A) which states:

Every person who sells or imports tires ․ that do not have a minimum depth of 3/32” ․ shall pay a fine of $10.00 per tire.

The court rejected this interpretation of the statute as implausible on the strength of the second sentence of Article 19(A) which states:

This provision shall apply to those who fail to comply but have not had their bond executed, according to what is pointed out in Article 5(D) [which requires all tire importers to post a bond].

It read that provision as making the penalty applicable only to those who have filed bonds, i.e., importers of used tires.

We agree with the district court’s interpretation. The reference to “those ․ who have not had their bond executed” and the cross-reference to Article 5(D) dealing with importers of used tires makes it clear that only those sellers of used tires who are also importers are the subject of Article 19(A). Moreover, as UTI points out, it would make little sense for the legislature to penalize sellers of noncomplying used tires taken in trade-in (i.e., locally-generated used tires) for to do so would simply accelerate the time when used tires are discarded as scrap and dumped in a landfill. On appeal, the Secretary merely reiterates that the penalty applies equally to sellers and to importers but has offered “only rhetoric, and not explanation.” See Chemical Waste Management, Inc. v. Hunt, 504 U.S. 334, 343, 112 S.Ct. 2009, 119 L.Ed.2d 121 (1992). We conclude, therefore, that Article 19(A) discriminates against sellers of imported used tires because only they and not sellers of locally-generated used tires are subjected to the penalty and, consequently, that Article 5(B) discriminates against importers of used tires because Law 171 singles them out in barring the import of tires with less than 3/32” tread depth.1

The district court, having concluded that Articles 5(B) and 19(A) are invalid, did not reach the bonding requirement under Article 5(D). That article provides that “[e]very tire importer shall file ․ a bond ․ equivalent to the total cost of the handling and disposal of the imported product. Should more than 10% of a representative sample of a shipment of imported tires fail[ ] to meet [the 3/32” standard] ․ the totality of the bond shall be executed.” Plainly the bonding requirement imposes burdens, costs and risks on importers of used tires not borne by sellers of locally-generated used tires and thus provides added support for the conclusion that Articles 5(B), 5(D) and 19(A) together facially discriminate against interstate commerce.

The inexorable increase in the volume of solid wastes and the health and environmental consequences attendant on their disposal present legislatures and courts with vexing problems. See Philadelphia v. New Jersey, 437 U.S. 617, 630, 98 S.Ct. 2531, 57 L.Ed.2d 475 (1978) (Rehnquist, J., dissenting). We may assume that Puerto Rico’s purpose in enacting Law 171 was to serve the best interests of all its citizens. But no matter how laudatory its purpose, “it may not be accomplished by discriminating against articles of commerce coming from outside the [Commonwealth] unless there is some reason, apart from their origin, to treat them differently.” Id. at 626-27, 98 S.Ct. 2531.2 In Philadelphia, the Supreme Court struck down a New Jersey statute that prohibited the importation of waste originating out of state. The crucial question, the Court said, was whether the statute was “basically a protectionist measure, or whether it can fairly be viewed as a law directed to legitimate local concerns, with effects upon interstate commerce that are only incidental.” Id. at 624, 98 S.Ct. 2531. To answer that question, the Court saw no need to resolve the dispute between the parties whether the purpose was to serve parochial economic interests or to save the environment for “the evil of protectionism can reside in legislative means as well as legislative ends.” Id. at 626, 98 S.Ct. 2531. New Jersey’s law, it held, fell within the area that the Commerce Clause puts off limits to state regulation because it “imposes on out-of-state commercial interests the full burden of conserving the State’s remaining landfill space.” Id. at 628, 98 S.Ct. 2531.

Puerto Rico’s legislation barring the importation of certain used tires is essentially indistinguishable from New Jersey’s.3 It, too, places the burden of conserving its landfill space on those engaged in interstate commerce, the importers of used tires. And it is essentially indistinguishable from the Alabama statute imposing an additional disposal fee on wastes generated outside the state, struck down in Chemical Waste. See also Fort Gratiot Sanitary Landfill, Inc. v. Michigan Dept. of Natural Resources, 504 U.S. 353, 112 S.Ct. 2019, 119 L.Ed.2d 139 (1992) (striking down statute barring disposal of solid waste generated in another county); Trailer Marine Transport Corp. v. Rivera Vazquez, 977 F.2d 1, 10 (1st Cir.1992). The costs associated with the required bond and the penalty upon the sale of noncomplying imported tires, moreover, resemble a tariff on goods that may be lawfully sold in the state because they are imported from another state, “[t]he paradigmatic example of a law discriminating against interstate commerce.” West Lynn Creamery, Inc. v. Healy, 512 U.S. 186, 193, 114 S.Ct. 2205, 129 L.Ed.2d 157 (1994). Because the Secretary has failed to come forward with a showing that Articles 5(B), 5(D) and 19(A) advance a legitimate local purpose that cannot be adequately served by reasonable nondiscriminatory alternatives, see New Energy Co. v. Limbach, 486 U.S. 269, 278, 108 S.Ct. 1803, 100 L.Ed.2d 302 (1988), they cannot withstand scrutiny under the Commerce Clause.4

UTI’S CROSS-APPEAL

UTI cross-appeals from the district court’s denial of injunctive relief against enforcement of Articles 6 and 17. We review the denial of a preliminary injunction for abuse of discretion. See Ross-Simons of Warwick, Inc. v. Baccarat, Inc., 102 F.3d 12, 16 (1st Cir.1996). The appealing party “bears the considerable burden of demonstrating that the District Court flouted” the four-part test for preliminary injunctive relief. E.E.O.C. v. Astra USA, Inc., 94 F.3d 738, 743 (1st Cir.1996). That test requires plaintiff to show probability of success on the merits as well as irreparable injury, the balance of harm tipping in plaintiff’s favor, and absence of adverse effect on the public interest. See, e.g., Starlight Sugar, Inc. v. Soto, 114 F.3d 330, 331 (1st Cir.1997).

Article 6 imposes a charge on each imported tire, whether new or used, varying with the dimension of the wheel rim. The revenue received from this charge is placed in an Adequate Disposal Tire Handling Fund, created under Article 17, to subsidize the cost of processing and recycling used tires. The district court held that Article 6 does not discriminate against interstate commerce because the charge is imposed on all tires entering Puerto Rico, no tires being manufactured in Puerto Rico. See Exxon Corp. v. Governor of Maryland, 437 U.S. 117, 125, 98 S.Ct. 2207, 57 L.Ed.2d 91 (1978). UTI argues that the charge discriminates because it is not imposed on locally-generated tires. Those tires, of course, pay the charge when they enter Puerto Rico as new tires. The district court found that those tires nevertheless enjoy an economic advantage because the charge is not passed on in the price of locally-generated used tires. Whatever the basis for that finding, we find nothing discriminatory in a one-time charge imposed on the importation of every tire, new or used. The only used tires that may enjoy an advantage are those that were imported new or used before Law 171 became effective (some of which were presumably imported by UTI). But their advantage is temporary and is the result, not of discrimination, but, rather, of the inevitable phasing in of the new law. Because we find that Article 6 “regulates evenhandedly to effectuate a legitimate local public interest, and its effects on interstate commerce are only incidental,” Pike v. Bruce Church, Inc., 397 U.S. 137, 142, 90 S.Ct. 844, 25 L.Ed.2d 174 (1970), we affirm the district court’s ruling denying injunctive relief.

Article 17(A)(1) provides for the distribution out of the Adequate Disposal Tire Handling Fund of the revenue derived from the import charge. Out of the revenue collected, handlers of tires to be processed or recycled in Puerto Rico are to receive a maximum of 91% of the handling and disposal fee and exporters up to 46%. UTI contends that this provision facially discriminates against tire exporters. The district court found, and it is not disputed, that UTI is not a scrap tire exporter and thus not hurt by the law. Accordingly, it lacks standing to attack this article. See Lujan v. Defenders of Wildlife, 504 U.S. 555, 560-61, 112 S.Ct. 2130, 119 L.Ed.2d 351 (1992).

UTI seeks to avoid its disability by arguing that Article 17 together with Article 6 create a tax-subsidy program similar to that found to be invalid in West Lynn Creamery, Inc. v. Healy, 512 U.S. 186, 114 S.Ct. 2205, 129 L.Ed.2d 157 (1994). West Lynn struck down a Massachusetts milk pricing order which imposed an assessment on all milk sold by dealers in Massachusetts, two-thirds of which came from out of state, and then distributed all of it to Massachusetts dairy farmers. Even though the assessment and the subsidy, separately, could be lawfully enacted, together they constituted a scheme under which out-of-state producers were required to subsidize competition by local high cost dairy farmers, neutralizing advantages possessed by lower cost out-of-state producers. Id. at 194, 114 S.Ct. 2205. The Puerto Rico import charge is distinguishable because it does not subsidize local dealers at the expense of those engaged in interstate commerce.5

CONCLUSION

We therefore AFFIRM the district court’s order respecting injunctive relief.

FOOTNOTES

1. Because no new tires are manufactured in Puerto Rico, all new tires are imported along with used tires. New tires in due course enter the local trade as locally-generated used tires when they are taken in trade-in or bought for resale by local tire dealers. At that point, they compete with imported used tires.

2. “Puerto Rico is subject to the constraints of the dormant Commerce Clause doctrine in the same fashion as the states.” Trailer Marine Transport Corp. v. Rivera Vázquez, 977 F.2d 1, 7 (1st Cir.1992).

3. The Secretary urges us to apply the balancing analysis explicated in Pike v. Bruce Church, Inc., 397 U.S. 137, 142, 90 S.Ct. 844, 25 L.Ed.2d 174 (1970). That analysis-weighing burdens against benefits-is inapposite, however, because this is not a law that “regulates evenhandedly to effectuate a legitimate local public interest” whose “effects on interstate commerce are only incidental.” Id. at 142, 90 S.Ct. 844. While we do not doubt the benefits to Puerto Rico’s citizens from extending the useful life of their landfills, the Philadelphia line of cases teaches that the Commerce Clause does not permit those benefits to be achieved at the expense of interstate commerce through discriminatory legislative means.

4. Severability is not an issue. Article 22 states: “The provisions of this Act are independent from one another, and should any of its provisions be declared unconstitutional ․ the decision ․ shall not affect or invalidate any of the remaining provisions, unless the Court’s decision so state[s] expressly.”

5. The foregoing discussion sufficiently disposes of UTI’s claim that Articles 6 and 17 violate the due process and equal protection clauses.

SCHWARZER, Senior District Judge.

Howard LEVY, Appellant,

v.

The TRAVELERS INSURANCE COMPANY and Aetna Casualty and Surety Company, Appellees.

Bob Zwicky of Law Offices of DeCesare & Salerno, Fort Lauderdale, for appellee/The Travelers Ins. Co.

Jeffrey W. Johnson and J. Edward Herndon of Hinshaw, Culbertson, Moelmann, Hoban & Fuller, Boca Raton, for appellee/Aetna Cas. and Sur. Co.

DOWNEY, Judge.

The insured, Howard Levy, appeals from a final order dismissing his complaint against appellees, Travelers Insurance Company and Aetna Casualty & Surety Company, in which he sought personal injury protection (PIP) benefits. Levy, who sustained injuries in an automobile accident, alleged that he had automobile insurance policies with Travelers and Aetna that included PIP coverage in full effect at the time of the accident. He claimed that he applied for benefits under the policies but that Travelers and Aetna refused to pay them. The trial court dismissed Levy’s *191 complaint based on the five-year statute of limitations, section 95.11(2)(b), Florida Statutes (1981).

All of the parties agree that the five-year statute of limitations is applicable to this contract action. They differ, however, in the event which triggers the commencement of the five-year period. Appellees contend the statute commences tolling upon the occasion of the accident giving rise to the claim; while appellant argues that the statute does not commence running until the contract is breached. We hold that the tolling of the five-year statute of limitations commences upon the breach of the insurance contract.

In opting for the date of accident as the critical date, appellees rely upon Fladd v. Fortune Insurance Company, 530 So. 2d 388 (Fla.2d DCA 1988), wherein the Second District Court of Appeal held that the five-year statute of limitations applicable to an action against an automobile insurer for breach of contract for failure to pay PIP benefits commenced to run on the date of the accident, rather than the date when benefits under the policy became overdue. The Fladdcase, in turn, relied upon State Farm Mutual Automobile Insurance Co. v. Kilbreath, 419 So. 2d 632 (Fla. 1982), in arriving at its conclusion. Kilbreathinvolved a cause of action for uninsured motorist (UIM) coverage, which the supreme court described as a cause of action that stems from plaintiff’s right of action against the tortfeasor and, thus, arises on the date of the accident. As the court said in that case, “the uninsured motorist statute gives the insured the same cause of action against the insurer that he has against the uninsured/underinsured third party tortfeasor for damages for bodily injury.” Id. at 632, 633.

The cause of action in this case is a first party claim in contract for failure to pay the contractual obligation for personal injuries sustained, regardless of fault. The coverage is mandated by section 627.736(1), Florida Statutes (1981), in all policies complying with the security requirements of section 627.733, Florida Statutes. With regard to the payment of PIP benefits, section 627.736(4)(b) provides:

Personal injury protection insurance benefits paid pursuant to this section shall be overdue if not paid within 30 days after the insurer is furnished written notice of the fact of a covered loss and of the amount of same.

It is apparent that, pursuant to the statute, the insurer has no obligation to pay benefits to the insured until thirty days after receipt of the insured’s claim. We see no reason to depart from the usual and customary rules regarding the application of the statute of limitations to insurance contracts unless there is an exception brought about by the nature of the claim, as in the UIM instance set forth in Kilbreath. For a clear exposition of the dichotomy involved in application of the statute of limitations to tort and contract claims, see Fradley v. County of Dade, 187 So. 2d 48 (Fla.3d DCA 1966). The issue presented here has also been examined and elucidated in Micha v. Merchants Mut. Ins. Co., 463 N.Y.S.2d 110, 94 A.D.2d 835 (3 Dept. 1983), wherein the court stated:

Turning now to the accrual date, it is the general rule that “[i]n contract cases, the cause of action accrues and the Statute of Limitations begins to run from the time of the breach * * * * (Krassner & Co. v. City of New York, 46 N.Y.2d 544, 550, 415 N.Y.S.2d 785, 389 N.E.2d 99). Application of this principle mandates rejection of the accrual date urged by defendant, for at the time of the accident defendant owed no contractual obligation to pay first-party benefits, and, therefore, it had not yet breached any contractual obligation. Defendant’s obligation to pay the first-party benefits required by its policy arose “as loss [was] incurred” and benefits “are overdue if not paid within thirty days after the claimant supplies proof of the fact and amount of loss sustained” (Insurance Law, § 675, subd. 1; see, also, Montgomery v. Daniels, 38 N.Y.2d 41, 47, 378 N.Y.S.2d 1, 340 N.E.2d 444). Interest on the benefits begins to accrue when the payment is overdue (Young v. Utica Mut. Ins. Co., 86 A.D.2d 764, 448 N.Y.S.2d 83), and *192 we conclude that an insured’s cause of action to recover the unpaid benefits accrues at the same time.

See also Rowland v. Safeco Insurance Co. of America, 634 F. Supp. 613 (M.D.Fla. 1986); Special Tax School Dist. No. 1 of Orange County v. Hillman,179 So. 805, 131 Fla. 725 (1938).

Accordingly, while recognizing conflict with the decision in Fladd v. Fortune Insurance Company, 530 So. 2d 388 (Fla.2d DCA 1988), we hold that the order appealed from is erroneous in that it relies upon the date of the accident giving rise to the PIP claim rather than the date of the breach of the contract by the insurers.

REVERSED.

HERSEY, C.J., concurs.

FRANK, RICHARD H., Associate Judge, dissents, with opinion.

FRANK, Associate Judge, dissenting.

I adhere to my concurrence in Fladd v. Fortune Insurance Company, 530 So. 2d 388 (Fla.2d DCA 1988).